- Home

- Rudy Rucker

Mathematicians in Love Page 2

Mathematicians in Love Read online

Page 2

“I saw you listed as a student of Roland Haut’s,” said Alma, circling me, sizing me up. “And I found out you had an appointment with him today. I can’t believe we never ran into each other before.”

“This place is too big,” I agreed. “I’m glad to see you.” I’d always been interested in Alma Ziff, but too shy to talk to her. She was intimidating in the lineup, with a loud mouth and usually some hard-looking older surf-rats at her side. Guys who wore shades in the water and preferred to speak Spanish. Indeed, I’d left that one beach party soon after I heard Alma’s brother Pete and one of his brahs say they wanted to “kick the pinche hairfarmer’s culo" Pete was a foul-mouthed long-haired beanpole, notorious on the scene, a stoner/surfer/biker/dreg with a beat-up motorcycle sporting a surfboard rack. His comrade that night had been an ugly gnome with a pompadour and giant grommets set into his earlobes.

In any case, Alma was alone with me now, and all smiles. “What have you heard about universal dynamics?” I asked her.

“I saw that article in the San Francisco Chronicle last month, and I looked at the introduction on Roland Haut’s Web site. But Buzz needs it in your own words.” She tapped the camera at her temple. “Tell us, Bela. I’m vlogging you.”

“All right,” I said, standing up straight for the camera, delivering the party line. “Plants and animals, the weather, political movements, your personal shifts of mood—all of these are what we might call chaotic dynamical systems. The key new insight is that any given dynamical system can be precisely modeled by a wide range of other dynamical systems, often of a quite different kind. Recently my thesis adviser Roland Haut proved that real-world orchid blossoms have the same shapes as computer-simulated water splashes. That was the first big success for universal dynamics. We’re expecting many more to come. We’ll read the weather in a teacup; watch a flapping flag for a medical diagnosis; model the legislature as a pile of rotting fruit. Am I talking too fast?”

“Thank you, Bela Kis,” intoned Alma.

“You said it wrong,” I put in.

“What?”

“My last name. You said ‘kiss,’ but it’s ‘keesh.’ Means ‘small’ in Hungarian. Kiss the Kis and see him grow.”

"Be-la.” Her voice was sweet music. “Can I follow you inside? I want to see some demos of, like, universal dynamics predicting something.”

“If Roland says it’s okay, I can show you the splashes that look like orchids.”

“Good. And maybe something newer?” Alma stepped close and ran her hand across my biceps. “Are you still surfing?” “Lately I’m always worrying about my thesis. And Ocean Beach is so gnarly in the winter.”

“I was there last month with my big brother Pete and his friend Wrong Wave Jose. They came up from Cruz. They’re both working on a fishing boat now. At least I hope it’s a fishing boat.”

“I think I’ve met them.”

“Yeah, they were always out at the Point with me. And that time you were talking to me at the beach party? Pete looks like a crusty long-haired dreg but he has a motorcycle, and Jose is—” “The aggro guy with the giant holes in his ears? Can he even speak English?”

“Oh, did he scare you, Count Dracula? Pete and Wrong Wave Jose aren’t vicious, they’re just shy. Poor self-esteem. Pete’s had a lot of problems.” Women always cover for their loser friends and relatives. You gotta love them for that.

“Jose has this not-so-secret crush on me,” continued Alma.

“Even though he’s utterly, totally out of the question. Sorry, Jose! I’m looking for a handsome boy with a good future. I learned all about it in this course I took last fall. Rhetorics of Sexual Exchange.”

“It’s okay that I’m part Chinese?”

We were in Pearce Hall now, riding the elevator to the tenth floor. Alma gave me this goofy smile. “It’s a plus.” She rose up on her toes and kissed my cheek. “And you are cute.”

“Thank you.” My heart was beating fast. I hadn’t had a date in months. And here I was alone with a woman in a metal box. Wonderful. I smelled the faint scent of Alma in the air: her breath, perfume, and hair spray.

I went ahead and brought Alma into Haut’s office with me. He was a stocky man with dark hair worn in an old-fashioned pageboy. Every now and then he’d go off the deep end and spend a few weeks in the psych ward. Right before his last breakdown, he’d shed his glasses for corneal surgery, as if to look less like a mathematician.

“This is my friend Alma from Santa Cruz,” I told Haut. “Alma, this is Roland.” I noticed that the light on the side of the camera behind Alma’s ear was still glowing. She’d been vlogging me in the elevator. So what.

Haut was forty, but he liked for students to call him by his first name—not that we wanted to. He had a basic coldness about him, and he could be quite cutting if riled. But people forgave him everything. He was a genius, a fount of fascinating new ideas.

“Why?” said Haut testily, meaning why had I brought Alma to meet him. He was sitting with his back to the window at a long desk scattered with pieces of paper and natural curiosities. Seashells, bits of driftwood, oddly striated rocks, dried seaweed, seedpods, animal teeth, crystals. On his left was a sunlit wall covered with orchids growing in little tubes.

Pinned up next to each plant was a graphical image of a computer simulation of a water splash shaped exactly like the plant’s blossom. Like I’d told Alma, this was the big success of universal dynamics so far. Two years ago, Roland had used the equations of fluid flow to predict the patterns of orchid growth. And for this work he’d won the Fields Medal—which is a very big deal in mathematical circles. Haut hadn’t yet published another result that dramatic, but he was hinting that something new was in the works. Something about crystals and discrete decision systems. But the details were for him to know and the rest of us to find out. He was secretive about his research, even among his students.

As usual, Haut was wearing high-quality yuppie clothes: a pink silk shirt with a green bow tie, black velvet plus fours, ar- gyle cashmere knee-socks, and red leather running shoes. (Note that the tastes and fashions of my birth-world differed a bit from those of the world in which I describe my adventures for you, dear reader.)

Haut was fastidious about his appearance, in fact he had a full-length mirror beside his door. Mathematics had been good to him. But it hadn’t done much for his personality.

“Why, Bela?” repeated Haut, stubbornly hassling me for bringing Alma along. As if it was this huge deal. His eyes hadn’t focused in on us, he was doing his zillion-mile stare, possibly watching himself in the mirror, which was positioned in such a way that he could see himself and the window behind him.

“I told her what a freak you are, and she didn’t believe me,” I rapped out, expecting it to come across as a joke. My idea was to break the negative loop of contempt and resentment that Haut and I had gotten into. I was fantasizing that we were both so socially inept that normal standards of politeness didn’t need to apply.

“Believe it,” said Roland, smiling with his teeth. “Can you get Bela to start his thesis, Alma? We’re not the only ones working in this area. The Stanford team might beat us out. Time is of the essence.”

“I’m powerless over the boy,” said Alma. “It’s an honor to meet you, Professor Haut. The thing is, I’m reporting a little segment on universal dynamics for this Humelocke-based webzine called Buzz?” She touched the camera poking out beside her eye. “Do you mind that I’m vlogging you?”

“Call me Roland.”

“I was wondering if I could show her the universal dynamics lab,” I suggested.

“No,” he said coldly. “Some of the work’s confidential. You know that, Bela.”

“But not the orchid simulation. That was on TV.”

“I don’t have time to supervise what you show her. Now, Alma, if you could wait outside for a minute, Bela and I have to talk. You’ve seen enough, yes?”

“Thank you, Professor Haut,” said Alm

a brightly.

“Roland,” he corrected. “You’re beautiful. Au revoir.” He gestured at me to close the door with Alma on the other side of it.

As soon as we were alone his face turned dark. “Where do you get off calling me a freak? And in front of a camera. Vlogging? This isn’t an art school.” The barking words echoed in the little room.

“I thought—”

“You don’t think, Kis, you feel. You’re conscious only of your needs. You have no awareness of other minds. When cornered, you mimic intelligent behavior. But I’ve seen no evidence that you think. Or am I wrong? Do you finally have something substantial to show me?”

The savage outburst wounded me. I fumbled my notebook open to my most recent drawing and tried to say something, but there was a lump in my throat. “I’ve been thinking about sheaves of fiber bundles connecting hyperplanes to these little Dr. Seuss seeds that—” I managed, and then my voice broke. I admired this man’s work so much, and he hated me. My own stupid fault.

“You’re emoting,” said Haut coldly. “In hopes of provoking pity. No use. I won’t carry you any longer, Bela. Please look for a new adviser. And if you can’t find one, settle for the master’s degree you’ve already got. That’s enough for teaching high school or community college.”

Wordlessly I stumbled from his office. On the way out I glimpsed myself in Haut’s wall mirror. I looked pathetic. Alma was right there in the hall. Her face softened when she saw me.

“He harshed on you? Poor Bela. Here.” She fished a fashionably lacy hankie from her purse.

“Don’t need it,” I said, rubbing my eyes in the crook of my arm. Following an obvious chain of association, I was remembering all the times my father had yelled at me and called me an idiot. I was starting to get mad. “That prick Haut. He fired me.” I glanced around; nobody else was in the hall. “I don’t need this. I’m a musician as well as a mathematician, you know. Come on, I’ll let you tape as much of his fucking lab as you like. It’s in the basement.”

“Right on.” Alma’s camera was still running.

At some level, I must have been riding the Tao, for we were alone in the elevator again. Once more Alma kissed me, and I kissed her back. Lips and tongue. In a way, I had a lot going for me. I’d done something outrageous and had been punished— so she was both impressed and sympathetic. Also I was about to escort her into a place she wanted to see.

“I like elevators,” I said when we paused for breath. “They’re a temporary autonomous zone outside of ordinary spacetime.”

“And you know it’s going to be of a limited duration,” added Alma. "So things can’t get too seriously out of hand.” She started laughing, fending me off from kissing her again. “I still can’t believe you said that to your thesis adviser. ‘I told her what a freak you are, and she didn’t believe me.’ Did you want him to drop you?”

I had to think about that for a second. "Sounds that way,” I said finally. “You are what you do. But now I wish I hadn’t done it. I’ve got this feeling I can still turn my thesis around. But Haut might make it hard for me to get my work approved.”

“Especially after you let me webcast his private goodies,” said Alma. We were stepping out in the Pearce basement. We passed a couple of lit-up open computer labs; at the end of the hall was the universal dynamics lab, sealed off with a metal door. “I don’t want to get you in more trouble,” continued Alma, holding my arm with both hands. “This story isn’t that important to me. I’m only doing it as a favor for my roommate Leni Pex. She hosts Buzz on a server in our apartment. Mostly just students read it. If you’re scared, let’s not bother.”

Even as Alma was saying all this, she was marching me towards that metal door. Body rhetoric. And I was fully going for it, eager to show her my spunk. Of course I realized that once her camera images were posted on Buzz, Haut would hear about them—there are no secrets on the Web. But I had this reckless urge to piss the man off. Yeah, Haut would be mad, but he’d probably get over it. It wasn’t like I was planning to show Alma anything that hadn’t aired a dozen times before.

“Nudge some of your hair forward so your camera doesn’t stand out so much,” I told Alma. “We’re goin’ in.”

I punched my keycode into the door’s pad and greeted the woman proctoring the lab, a fellow first-year grad student sitting at a desk studying.

“Hi, Lakshmi,” I said. “I want to show Alma around. She’s

working on some applications. I checked with Roland.” Sort of true.

“Fine,” said Lakshmi, hardly looking up from her topology textbook. “Just sign in.”

So we signed in, using our real names. I led Alma over to Haut’s multiprocessor supercomputer, funded by a fat grant from the NSF. As it happened, my own login ID wasn’t working—already disabled by Haut? So I used his login and password, which I happened to have learned by watching him log in from his office. It was easy: user ID rolandhaut; password Iamagenius.

I stepped Alma through the standard demo that Haut always showed his interviewers, split-screen pairs of water splashes and orchid blossoms, with each half of the screen containing an image and some equations. The paired images were similar in shape, although not in texture and color—you could tell that the ones on the left were simulated water and the ones on the right were actual plants. And of course the paired equations were totally different. I explained to Alma that Roland Haut had gotten the Fields Medal for proving that the equations really were at some deep level the same, which in turn implied that the forms shown in the images could indeed be made identical, were it possible to precisely match the equations’ parameters.

“Do you have any other pictures?” asked Alma, not interested in the mathematics.

I moused around and found a file labeled aprilvote.nbin Haut’s documents folder, time-stamped with today’s date. I hadn’t seen this one before, or even heard about it. I was intensely curious to see it—keep in mind that, despite our personal differences, I was a passionate admirer of Roland Haut’s work. So I went ahead and launched aprilvote. nb, with Alma and her camera peering over my shoulder. I figured that later, if necessary, I’d have time to tell her not to post these images. But right now, I just had to look.

The left side of the screen showed a beautiful simulation of frost forming on a windowpane. The right side of the screen showed a table of precinct-by-precinct vote tallies for Van Veeter and Karen Barbara. A simulation of today’s election. At the bottom of each image were, once again, sets of equations.

As the fingers of frost grew and exfoliated, the table entries changed, the numbers spinning like digits on a hit counter. The way my brain is wired, I often imagine sounds when I look at pictures. And the sounds of the pictures were matching pings and crackles. After a minute or two of frenetic activity the two on-screen windows settled down. The frost pattern looked like a duck or maybe a rabbit. And Karen Barbara was the election winner by a razor-thin margin of seventy-nine votes.

“Is that for real?” whispered Alma.

“You absolutely can’t put this on Buzz,” I said. “It’s Haut’s next research paper.”

Physicists conjecture that when a test individual B falls past the event horizon of a black hole, he himself doesn’t immediately notice this. He’s doomed, but at first only his stationary observer A knows.

“I’m vlogging in real time,” said Alma in a small voice. “My camera has a wireless link; it posts an upload every ten seconds. I thought you understood that.”

Lakshmi the lab proctor’s phone was ringing. Could it already be Haut? We didn’t stick around to find out.

Outside Pearce Hall, I got Alma to turn off her camera and put it away, and then I had her phone her friend Leni Pex and ask her to remove the hoarfrost-and-voting movie from the Buzz server. Listening to Alma’s end, I gathered that Leni was sitting at her keyboard, doing the delete right away, and, then, just for the hell of it, checking how many downloads the april-vote segment had go

tten in the minute or so it had been up and—ow—it was 476.

“That many?” I said to Alma as she put away her cell phone. "Four freaking hundred and seventy screw-me six?

“The Buzz server runs this news-feed software? A client can, like, register their preferences so that their browser gets an alert whenever news about a favorite topic appears on any news server. And then their browser can do an automatic download. And there’s a lot of interest in the election today. So . . .”

I glanced up at Pearce Hall, wondering if Haut might just possibly be aiming a military-grade sniper rifle at me from his office window. An unexpected shoal of clouds had filled the sky with marbled gray. In my possibly-soon-to-be-exploded head I could hear guitar metal chords and a chorus chanting, “Paranoia, the destroyer,” at a rate of many, many repetitions per second—followed by the sudden crack of gunfire.

“Come on,” I said, cutting around to the other side of the tall cylindrical bell tower that stood next to Pearce Hall. Getting out of Haut’s line of fire. “Better here.” I took a big shaky breath.

“Lighten up, Bela,” said Alma. “Tell you what, I’ll take you surfing at Ocean Beach.”

“For sure,” I said guffawing sarcastically. “I don’t need to do no fuckin’ homework. I’m gettin’ expelled.”

“You don’t know that,” she said soothingly.

In the back of my mind I’d been going over the frost and voting equations I’d just seen, and now I was beginning to see the outlines of a miraculously simple geometric proof of why the two would be equivalent. What a radical concept. Haut was a genius. “I’m going to have to tell him that I’m really, really sorry,” I said.

“Not today,” said Alma. “Lie low. You think Barbara will really win by seventy-nine votes? Maybe Haut will thank you for getting his prediction out there. This could be good publicity for him. Maybe he was feeling shy.”

“Shy? Roland Haut?”

“Let it go, Bela. Be in the now. We’re going surfing. I hope you have a car?”

Million Mile Road Trip

Million Mile Road Trip Good Night, Moon

Good Night, Moon Transreal Trilogy: Secret of Life, White Light, Saucer Wisdom

Transreal Trilogy: Secret of Life, White Light, Saucer Wisdom Complete Stories

Complete Stories The Sex Sphere

The Sex Sphere Surfing the Gnarl

Surfing the Gnarl Software

Software Mathematicians in Love

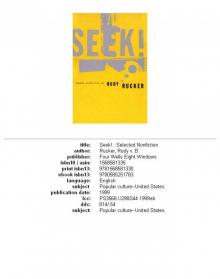

Mathematicians in Love Seek!: Selected Nonfiction

Seek!: Selected Nonfiction The Secret of Life

The Secret of Life The Hacker and the Ants

The Hacker and the Ants Postsingular

Postsingular Spaceland

Spaceland Transreal Cyberpunk

Transreal Cyberpunk Sex Sphere

Sex Sphere Spacetime Donuts

Spacetime Donuts Freeware

Freeware The Ware Tetralogy

The Ware Tetralogy Frek and the Elixir

Frek and the Elixir Junk DNA

Junk DNA White Light (Axoplasm Books)

White Light (Axoplasm Books) Nested Scrolls

Nested Scrolls Inside Out

Inside Out Where the Lost Things Are

Where the Lost Things Are Mad Professor

Mad Professor As Above, So Below

As Above, So Below Realware

Realware Jim and the Flims

Jim and the Flims Master of Space and Time

Master of Space and Time The Big Aha

The Big Aha Hylozoic

Hylozoic