- Home

- Rudy Rucker

Mathematicians in Love

Mathematicians in Love Read online

This is a work of fiction. All the characters and events portrayed

in this novel are either fictitious or are used fictitiously.

MATHEMATICIANS IN LOVE

Copyright © 2006 by Rudy Rucker

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book,

or portions thereof, in any form.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

A Tor Book

Published by Tom Doherty Associates, LLC

175 Fifth Avenue New York, NY 10010

www.tor.com

Tor® is a registered trademark of Tom Doherty Associates, LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Rucker, Rudy v. B. (Rudy von Bitter], 1946- Mathematicians in love / Rudy Rucker.—1st ed. p. cm.

“A Tom Doherty Associates book.”

ISBN-13: 978-0-765-31584-7 ISBN-10: 0-765-31584-X (acid-free paper)

1. Mathematicians—Fiction. 2. Interpersonal relations—Fiction. I. Title. PS3568.U298M38 2006 813'.54—dc22 2006005725

First Edition: December 2006

Printed in the United States of America

0987654321

For Sylvia, my true love

CONTENTS

1: Bela, Paul, and Alma 13

2: Cone Shell Aliens 55

3: Rocking with Washer Drop 98

4: Hypertunnel at the Tang Fat Hotel 146

S: Mathematicians from Galaxy Z 202

6: The Gobubbles 261

7: The Best of All Possible Worlds 326

“Where are we, then, if not in paradise?” he asked.

—from Jorge-Luis Borges, "The Rose of Paracelsus," Collected Fictions

1

Bela, Paul, and Alma

My tale begins on an alternate Earth in the university town that we called Humelocke, a close match for your Berkeley. And the book will end with me here in your San Jose, California, writing up my adventures—and preparing to move on.

To make my story easier to read, I won’t use each and every alternate place name we had on my original world. But I’ll keep “Humelocke,” in fond memory of that specific place and time where I first came to know wonder, madness, and love.

It was an April morning in Humelocke, and I was working on my Ph.D. thesis; that is, I was staring out my apartment window and imagining Minkowski hyperplanes buttressed by homotopy sheaves, with the whole twinkling cloud castle tethered to a trio of animated figurines shaped like, oh, a rake, a fish, and a teapot. Three morphons.

Say what? I’m a mathematician.

My thesis adviser, Roland Haut, had set me in pursuit of a fabulous mathematical unicorn called the Morphic Classification Theorem. I was up to my ears in student loan debt, and I wanted to finish very soon. Another doctoral candidate was on the hunt as well, Paul Bridge, who happened to be my roommate. Paul was making better progress.

As I thought of Paul, my view of mathematical paradise dissolved and I was staring at a puny tree in our apartment complex’s dingy courtyard. Mathematics lent even this humble object some borrowed glory. The leaf-bud-studded branches were rocking in the fitful spring breeze and, the branches being compound pendulums, their motions were deliciously chaotic. I savored the subtle whispering of the wind. Combining the sights and sounds, I could visualize the turbulent air currents in the wind-shadow of the tree: corkscrews and vortex tubes, realtime physical graffiti far gnarlier than the sheaves and hyperplanes I kept trying to dream. Why was I trying to outthink Nature? Why not embrace the world and go surfing?

I glanced down at my binder full of penciled thesis notes, with little turds of eraser rubber stuck to the pages. I had a nice big sketch of my latest image: the hyperplanes like disconnected floors of a building, the sheaves like bulbous elevator shafts, and the morphon figurines off to one side like control knobs. I dug it, but Roland Haut wouldn’t like it. My monthly meeting with him was in an hour. I seemed unable to produce the kind of thesis he expected. I’d lost my way in the enchanted forest and a magic pig was eating my lunch.

Literally. I could hear him behind me, rooting through the fridge, popping off a container’s plastic lid. It made a faint B-flat note.

“Leave the mashed peas alone, Paul. They’re mine.”

“I’ll only take half.” He was dipping the peas out with two fingers that he kept pressed together and slightly curved, as if to mimic a legitimate spoon. “How much did they cost?” asked Paul. “You can add half that amount to my share of the rent.”

“Plus a thirty-four-dollars-an-hour personal-shopper fee prorated for my twenty-seven minutes at the market plus eight-and- a-half percent sales tax, an eleven-percent convenience charge, and a per-transaction accounting charge of a dollar seventy-seven,” said I.

"How many items did you buy on that particular shopping trip?” challenged Paul. “If you’re charging for shopping time, you need to divide by the number of items you bought.” He mimed a brisk division-slash in the air, keeping his spoon fingers stiff and bent, the fingers clotted with green paste, wet with spit.

Paul’s wallet was on the counter, the wallet’s edges precisely aligned with the counter’s. I plucked it up and extracted a five- dollar bill. Even though Paul argued about money, he usually had some. His arguing was more for sport. My arguing, on the other hand, was more for money. I’m—call it frugal. I get that from my mother, Xiao-Xiao; she’s half-Chinese, a widow, runs a tiny eatery in the South Bay. My father, Tibor, had been a Hungarian computer-chip engineer and a willful tyrant. Right before his heart attack, he’d blown all of the family’s savings in Reno. Jerk. My big sister Margit and I had needed to take out big student loans to go to college.

“Peas all yours now,” I said, pocketing Paul’s five. A good deal. Although the mashed peas had been the tasty kind with the picture of sweet-pea flowers, they’d cost only $3.89, and were a week old, on the point of tasting metallic. I walked over to my desk by the window and put my worn spiral notebook into my knapsack.

“I get lichees,” said Paul, still at the fridge. He tipped some of my jellied lichees from their tub into his mashed-pea container, using his relatively clean thumb to coax them along. Although Paul was orderly with his possessions, he was a like a wild animal when it came to food.

“Help yourself,” I said, pulling back from being stingy. "What’s mine is yours.”

Paul drifted back to the kitchen table, his attention once again on the screen of his laptop. His hair was lank and medium length, of no particular color. He wore flesh-colored plastic glasses; he had the notion that a pinkish frame color made glasses less visible. When he was uneasy, he always adjusted his glasses, pushing the bridge higher on his nose. He had a firm, handsome mouth, although there was a slight gap between his front teeth. His short-sleeved white shirt was translucent, with his loop undershirt showing through. His neck usually had red razor rash. He was from Saint Matthews, Kentucky, and talked with a hint of a country accent. I’d heard another student say that Paul looked like a Bible salesman who rents a room in a house trailer from a retired school teacher and she catches him screwing her poodle dog. But that was going too far. Paul was a good guy. He wasn’t obese; he didn’t smell bad; he had a sense of humor.

Paul was my friend, and hip or not, he was a great person to hang out with, perhaps the most interesting person I’d met in my life. He was smart, well organized, and intellectually generous. Paul liked to hold forth to me on this work, showing me his latest pages and going over the details, but after a bit, his spaceship of thought would always lift off and leave me stranded on my own dark and lonely planet.

We each had our own take on how the big Morphic Classification Theorem should go: Paul’s thesis

was symbolic and analytic; mine was to be visual and geometric. We had radically different styles of doing math. I’d try to explain my drawings, he’d try to explain his tidy rows of symbols, but for all the communication we achieved it was like we were showing each other scratches and dings and barnacle clusters on rocks and seashells.

Paul had recently given a well-received math colloquium at Stanford on his preliminary results—even though I’d tried to talk him out of it, fearful as I was of being scooped. There was a big universal dynamicist at Stanford named Cal Kweskin; he and his student Maria Reyes were closing in on the Morphic Classification Theorem, too. I was kind of disorganized about attending conferences and seminars, so I hadn’t actually met those two even though I’d read, or had tried to read, their papers. Paul was a lot better at networking than I was.

It would have been hard for me to put together a good talk on my work thus far, although I did have some nice drawings scattered through my hundred or so penciled pages. Neither Paul nor Haut fully appreciated my pictures; Haut’s style of math was more like Paul’s than like mine. Haut kept asking me to prove a theorem. After six month’s work, I still didn’t have that one solid result to hang my Ph.D. thesis upon. Although I’d found some interesting conjectures, they remained stubbornly undecidable, in limbo, neither provable nor refutable.

Paul and I lived in the crummy old wood-shingled Ratvale student co-op with its gray carpeting on undulating floors and permanent smells of puke, pot, and cat piss.

How we two met is that we happened to sit next to each other at the math grad students’ orientation session. Paul endeared himself to me by spilling a full cup of coffee into the open knapsack sitting between his feet.

“You do that often?” I asked him.

He paused, analyzing the query. “Less often than once a month, more often than once a year,” he said finally. “Are you looking for a roommate?”

“Probably.” I liked the implicit fuck you in Paul’s narrowly logical answer. And I liked that, despite this bit of bravado, he looked even more anxious than me. Although I’d survived the math undergrad program at UC Santa Cruz, math at Humelocke was intimidating. The big leagues.

Paul and I chatted a little about our backgrounds. He’d started out as a chemistry major at the geek heaven of BIT, the Boston Institute of Technology, and had gotten bored with having to learn chemical recipes and compounds by heart. For him, math was easier—once he understood something, he could reproduce the proof, and there was nothing left to memorize. He’d switched over to mathematics his junior year in college.

“What kind of math are you interested in?” I asked him.

“Universal dynamics,” he said, and that sealed our partnership. Both of us had come to Humelocke in hopes of writing a thesis in this hot new field with the great Roland Haut.

Our shared dream had come true, but only Paul was making the most of it.

Walking down Telegraph Avenue towards campus, I bought a fat slice of squid pizza and an XL coffee. I was worried about my meeting with Haut. By now he was more than disappointed in me; he was contemptuous. And, for my part, I resented his attitude. I've never been one to take criticism calmly.

The only redemption would be to show Haut something amazing—which I seemed quite unable to do. I was still hoping to become a genius mathematician, but it was a lot harder than I’d imagined. What if Ma were right? She kept saying I should stop borrowing money for grad school and get a job at a high- tech company, like my thuggish cousin Gyula Wong, who was on the security staff at Membrain Products down in Watsonville; they made various kinds of sophisticated membranes for, like, drums, pumps, filters, electrical transformers, and medical apps.

As usual, Ginsberg Gate at the edge of campus was lined with people at card tables: army/gay/fraternity/anarchist/ Islamic/corporate recruiters and the like. I like the sounds of crowds, of the voices layering upon each other.

Today there was extra activity at the gate, stirred up by a hotly contested special election. The Humelocke district’s congresswoman had died in plastic surgery, and the vote for her replacement was today. A computer genius and self-made billionaire by the name of Van Veeter was running as a Heritagist, trying to win the spot from the painfully inept Common Ground Party candidate, Karen Barbara—for whom I was planning to vote.

There’d been so many gaffes and scandals involving Barbara that, inconceivable as it sounds, this time around a Heritagist had a chance at representing Humelocke. Our benighted country was three and a half years into the reign of the Heritagist Joe Doakes, the least intelligent and most repressive president ever. But even now, every election seemed to sweep more Heritagists into office—with no great hope for a Common Ground victory in the upcoming November national election. We’d suffered a series of terrorist attacks which had our citizens in a state of fear. Most recently a terrorist named Tariq Qaadri had blown up the Roebuck skyscraper in Chicago—and was still at large. Even though our troops had cornered Qaadri in Lilliputistan, he’d somehow escaped to a safe haven in Blefescustan, only to mastermind more bombings from there.

Instead of blaming President Doakes for Qaadri’s continued terror, the voters clung to Doakes the more. And it was looking like the Common Ground presidential candidate was going to be a patrician stuffed shirt named Winston Merritt, a painfully awkward man too polite to ask the hard questions about why Doakes didn’t catch Qaadri. Doakes’s only real liability was Vice President Frank Ramirez, an unpleasant character dogged by rumors of graft and of personal violence.

Although he was a Heritagist, our local congressional candidate, Van Veeter, was no extremist; he was a logical computer guy, seemingly quite honest. His reasons for wanting to be a congressman had to do with some quirk of corporate tax law that had particularly outraged him. He’d begun his career by patenting some clever new chip designs, and had built up a successful company called Rumpelstiltskin, making specialized chips for cell phones and other wireless devices. Recently Rumpelstiltskin had been using its sky-high stock to acquire several other companies. According to Veeter, there was one particularly obstreperous tax law relating to his maneuvers that had made him decide to go to Washington and debug the system. A lot of people seemed to like the idea of a geek debugging DC. There was even talk of having Veeter replace Ramirez on the national ticket for November. But first, of course, he’d have to win the Humelocke election today.

As I imagined yet another Heritagist victory, I seemed to hear a downward beep like a character dying in an arcade game, and a stomach cramp hit me. Coffee, pizza, stress. I darted into the student center for a pit stop. While I was washing up, I looked in the mirror, working on my self-esteem.

I liked what I saw. Bela Kis. Being three-quarters Hungarian and one-quarter Chinese, I have this nice warm skin color. I’ve been bleaching my thick, blunt-cut hair since high school. I have virile dark stubble on my jaw. I’m fit-looking, thanks in part to having taken up surfing in Santa Cruz. I play electric guitar well enough to have been in a little college band called E To The I Pi. And this particular day, I was wearing an orange plaid golf shirt and purple bell-bottoms which looked good on me.

In short, you’d never have guessed I was a math student. Maybe if I’d been all robotic and Martian and autistic like the others, then it would have been easier for me to prove the Mor- phic Classification Theorem. On the other hand, perhaps a truly radical proof could only come from a suave surf dog like me.

I headed up a grassy green slope towards the math building, Pearce Hall, a handsome relic of the NeoDeco 1970s, fully twelve stories tall, with chrome falcons decorating its cornices. I was avoiding thinking about Haut and the election by staring down past Humelocke towards the bay and San Francisco. It was a blue-sky day with puffy white clouds, the living air like cool clear water. A nice offshore breeze. Good day for Ocean Beach, over on the other side of San Francisco. I hadn’t been in the water all winter.

“Hi, Bela,” said a woman righ

t outside Pearce Hall, smiling at me. About my age, deep brown eyes. A wide mouth and fragile jaw. A dimple beside the corner of her lips. Wavy brown hair teased and sprayed into a fashionable shag with three streaks of blonde. A Peter Pan collar white shirt with an anarchist bomb drawn on the back in black marker-pen, a plaid red miniskirt worn backwards, gold golf shoes. Cute, hip, happening. A nice up-and-down rhythm in her voice. She seemed familiar, but— “Pleasure Point?” she said, making a wavy gesture with one hand. “Pink and green wetsuit?”

“Alma the local!” Of course. I’d occasionally seen her surfing at Santa Cruz, and one time we’d actually met at a beach party. Not that the locals down there mingled all that much with the college kids. They called us hairfarmers, even though most of us were dreggers, the same as them. “You’re a student at Hume- locke?” I asked Alma.

“My senior year. I’m—” she paused to giggle prettily. “A Rhetoric major. We studied this rant by one of the former math professors.”

She meant The Unabomber Manifestoby Ted Kaczynski, the most famous crazy mathematician of them all, one-time professor of our own University of California at Humelocke.

“My roommate says anyone who mails bombs to computer scientists can’t be all bad,” I said, thinking of Paul. “But, hey, that was last century. We’re too big for envy anymore. Thanks to universal dynamics, math is going to rule the world.”

“That’s what I was hoping to see you about! I’m reporting a feature on universal dynamics for this webzine called Buzz. It’s my final project for Sci Lies—what we call Rhetoric of Scientific Discourse.”

I noticed now that Alma was wearing a digital video camera tucked behind her ear. A little red diode glowed on its side. I’d looked at Buzz a couple of times. Cartoons, interviews, radical politics, minifictions. “You’re, like, stalking me?”

Million Mile Road Trip

Million Mile Road Trip Good Night, Moon

Good Night, Moon Transreal Trilogy: Secret of Life, White Light, Saucer Wisdom

Transreal Trilogy: Secret of Life, White Light, Saucer Wisdom Complete Stories

Complete Stories The Sex Sphere

The Sex Sphere Surfing the Gnarl

Surfing the Gnarl Software

Software Mathematicians in Love

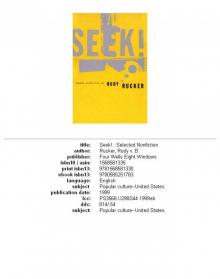

Mathematicians in Love Seek!: Selected Nonfiction

Seek!: Selected Nonfiction The Secret of Life

The Secret of Life The Hacker and the Ants

The Hacker and the Ants Postsingular

Postsingular Spaceland

Spaceland Transreal Cyberpunk

Transreal Cyberpunk Sex Sphere

Sex Sphere Spacetime Donuts

Spacetime Donuts Freeware

Freeware The Ware Tetralogy

The Ware Tetralogy Frek and the Elixir

Frek and the Elixir Junk DNA

Junk DNA White Light (Axoplasm Books)

White Light (Axoplasm Books) Nested Scrolls

Nested Scrolls Inside Out

Inside Out Where the Lost Things Are

Where the Lost Things Are Mad Professor

Mad Professor As Above, So Below

As Above, So Below Realware

Realware Jim and the Flims

Jim and the Flims Master of Space and Time

Master of Space and Time The Big Aha

The Big Aha Hylozoic

Hylozoic