- Home

- Rudy Rucker

Mad Professor Page 5

Mad Professor Read online

Page 5

“Elf Circle Farm,” said Bev. “I know all about the case. Like I said, I’m the county clerk. I can shuffle some papers, say a few words, and—zickerzack!”

So Bev and Jory married, and Jory took possession of his chosen portion of Gunnar’s land: the house, the creek, and the mushroom glen. They fixed the place up, and got a pair of cows for old times’ sake. Once or twice, Jory thought he detected a glitter of subdimensional ectoplasm in the barn where Uncle Gunnar had hung himself, but the shade spoke no more with his nephew. No need: Jory never again contemplated suicide.

In the evenings, comfortably tired from the light chores, he and Bev would sit around the crackling hearth drinking caraway-seed-flavored aquavit, spinning tales about Elfland, academia, and the Gold Country. Over time, Jory came to see himself as an incredibly wise and fortunate man, as did his new step-grandson Jack, who often came to visit in the summers.

Dropping the boy off, Jack’s mother Hilda always conversed pleasantly with Jory, realizing she owed him credit for her professional successes extending his rhizomal subdimension theory—not that she was ever able to replicate his antigravity breakthrough.

As for the alvar, they never returned—at least not to Elf Circle Farm.

And, oh, yes, Bev’s tail. It was there for good. During the first months of living on the farm, Bev hid the tail by wrapping it around her waist. But then, at Jory’s urging, she began letting it hang out. Her theater group approved.

PANPSYCHISM PROVED

“THERE’S a new way for me to find out what you’re thinking,” said Amy, sitting down across from her coworker Rick in the lab’s sunny cafeteria. She looked very excited, very pleased with herself.

“You’ve hired a private eye?” said Rick. “I promise, Amy, we’ll get together for something one of these days. I’ve been busy, is all.” He seemed uncomfortable at being cornered by her.

“I’ve invented a new technology,” said Amy. “The mindlink. We can directly experience each other’s thoughts. Let’s do it now.”

“Ah, but then you’d know way too much about me,” said Rick, not wanting the conversation to turn serious. “A guy like me, I’m better off as a mystery man.”

“The real mystery is why you aren’t laid off,” said Amy tartly. “You need friends like me, Rick. And I’m dead serious about the mindlink. I do it with a special quantum jiggly-doo. There will be so many apps.”

“Like a way to find out what my boss thinks he asked me to do?”

“Communication, yes. The mindlink will be too expensive to replace the cell phone—at least for now—but it opens up the possibility of reaching the inarticulate, the mentally ill, and, yeah, your boss. Emotions in a quandary? Let the mindlink techs debug you!”

“So now I’m curious,” said Rick. “Let’s see the quantum jiggly-doo.”

Amy held up two glassine envelopes, each holding a tiny pinch of black powder. “I have some friends over in the heavy hardware division, and they’ve been giving me microgram quantities of entangled pairs of carbon atoms. Each atom in this envelope of mindlink-dust is entangled with an atom in this other one. The atom-pairs’ information is coherent but locally inaccessible—until the atoms get entangled with observer systems.”

“And if you and I are the observers, that puts our minds in synch, huh?” said Rick. “Do you plan to snort your black dust off the cafeteria table or what?”

“Putting it on your tongue is fine,” said Amy, sliding one of the envelopes across the tabletop.

“You’ve tested it before?”

“First I gave it to a couple of monkeys. Bonzo watched me hiding a banana behind a door while Queenie was gone, and then I gave the dust to Bonzo and Queenie, and Queenie knew right away where the banana was. I tried it with a catatonic person too. She and I swallowed mindlink dust together and I was able to single out the specific thought patterns tormenting her. I walked her through the steps in slow motion. It really helped her.”

“You were able to get medical approval for that?” said Rick, looking dubious.

“No, I just did it. I hate red tape. And now it’s time for a peer-to-peer test. With you, Rick. Each of us swallows our mindlink dust and makes notes on what we see in the other one’s mind.”

“You’re sure the dust isn’t toxic?” asked Rick, flicking the envelope with a fingernail.

“It’s only carbon, Rick. In a peculiar kind of quantum state. Come on, it’ll be fun. Our minds will be like Web sites for each other—we can click links and see what’s in the depths.”

“Like my drunk-driving arrest, my membership in a doomsday cult, and the fact that I fall asleep sucking my thumb every night?”

“You’re hiding something behind all those jokes, aren’t you, Rick? Don’t be scared of me. I can protect you. I can bring you along on my meteoric rise to the top.”

Rick studied Amy for a minute. “Tell you what,” he said finally. “If we’re gonna do a proper test, we shouldn’t be sitting here face to face. People can read so much from each other’s expressions.” He gestured toward the boulder-studded lawn outside the cafeteria doors. “I’ll go sit down where you can’t see me.”

“Good idea,” said Amy. “And then pour the carbon into your hand and lick it up. It tastes like burnt toast.”

Amy smiled, watching Rick walk across the cafeteria. He was so cute and nice. If only he’d ask her out. Well, with any luck, while they were linked, she could reach into his mind and implant an obsessive loop centering around her. That was the real reason she’d chosen Rick as her partner for this mindlink session, which was, if the truth be told, her tenth peer-to-peer test.

She dumped the black dust into her hand and licked. Her theory and her tests showed that the mindlink effect always began in the first second after ingestion—there was no need to wait for the body’s metabolism to transport the carbon to the brain. This in itself was a surprising result, indicating that a person’s mind was somehow distributed throughout the body, rather than sealed up inside the skull.

She closed her eyes and reached out for Rick. She’d enchant him and they’d become lovers. But, damn it, the mind at the other end of the link wasn’t Rick’s. No, the mind she’d linked to was inhuman: dense, taciturn, crystalline, serene, beautiful—

“Having fun yet?” It was Rick, standing across the table, not looking all that friendly.

“What—” began Amy.

“I dumped your powder on a boulder. You’re too weird for me. I gotta go.”

Amy walked slowly out the patio doors to look at the friendly gray lump of granite. How nice to know that a rock had a mind. The world was cozier than she’d ever realized. She’d be okay without Rick. She had friends everywhere.

MS FOUND IN A MINIDRIVE

In the summer of 2004, while traveling in the West, I found a small electronic device in a meadow near Boulder, Colorado. It was a fingertip-sized minidrive of the type that can be plugged into the port of a laptop computer. There was but a single document stored upon the drive: the story that I have appropriated and printed below. The actual author, one Professor Gregge Crane, seems to have gone permanently missing.

—R. R.

THIS summer I was asked to submit a piece for an anthology of tales inspired by Edgar Allan Poe. The publisher’s somewhat tendentious idea for the book was that each contributor should create a story relating to one and the same unfinished Poe manuscript.

The seed-fragment in question, known as the “The Lighthouse,” takes the form of a few journal entries by a disinherited young noble (poor Eddie’s perennial theme!) who has signed up for a stint as a solitary lighthouse keeper on a shoal of rock in some far Northern sea.

The reader quickly senses there will be trouble within and without. On the one hand, “there is no telling what may happen to a man all alone as I am—I may get sick, or worse . . .” and on the other, “the sea has been known to run higher here than anywhere with the single exception of the Western opening of the Straits of Magellan.”

There’s something unsettling about the lighthouse’s construction. The space within the tower’s shaft extends so low that “the floor is twenty feet below the surface of the sea, even at low tide. It seems to me that the hollow interior at the bottom should have been filled in with solid masonry. Undoubtedly the whole would have been rendered more safe—but what am I thinking about?”

One final, portentous observation: “The basis on which the structure rests seems to be chalk. . . .”

And here Poe’s fragment ends.

+ + +

I’m a well-connected scholar of American Literature, which is why I was offered the opportunity to join the anthology. But I’m not a man with a mad imagination. Transmuting so slight a start into a full-blown weird tale seemed a tall order for me. Although I love writing, and writers, I’ve never quite found my own connection to the starry dynamo of night.

Be that as it may, I was gung-ho to be part of the “Lighthouse” anthology. My chance to be a fiction writer at last! It struck me that I’d do well to attend a writer’s workshop—and for sentimental reasons, I settled on the summer program at the Naropa Institute in Boulder.

You could say I’m a bit of literary groupie. I’m bisexual of course, and I’ve had my share of rolls in the hay with writers, each time hoping, I suppose, that something of their essence might rub off.

As it happens, the most famous writer I ever slept with was William Burroughs. This was in the early 1980s—I was attending a Modern Language Association conference at Colorado University, and Bill was in residence for the summer as part of Naropa’s burgeoning Jack Kerouac Disembodied School of Poetics. I knew of this, and one of my old lovers used her not inconsiderable charms to get us into a cocktail party for the innermost circle of Boulder bohemia. Bill was there, I made a favorable impression, and voilà, the Beat master and I ended up in his room at the Boulderado Hotel, sipping bourbon, smoking low-grade marijuana, and making languid love. A night to treasure for my entire life, a night signifying that I too have had a purpose on this lonely planet.

And so this June, once my academic duties had ended for the term, I repaired to the Boulderado Hotel, this time as a paying guest, with a sheaf of Naropa University orientation papers in my briefcase.

Much of school’s opening session that afternoon had consisted of perky functionaries reciting lists of rules. Not like the crazy eighties. Naropa had once been the outriders’ beacon; had the rugged old tower toppled to become a mere breakwater in the safe harbors of American mass culture? I only hoped that some esoteric possibilities remained.

Naropa’s Tibetan Buddhist founder wrote of a paradoxical land hidden outside, or next to, or beneath our daily reality. Shambhala—which Westerners call Shangri La.

The Beats had crumbled, but perhaps the door to Shambhala remained. I thought of Poe’s doomed lighthouse, and of the mysterious chamber at its base. I was filled with a numinous sensation that somehow everything was going to fit. Looking around at my fellow students, I realized I was one of the oldest customers in the house. Very well, but I was young at heart, ready to become a writer at last.

In a celebratory mood, I drank half a bottle of champagne at the hotel bar and then, on a whim, I went up to the fifth floor and stood outside the corner room where Bill and I had coupled so thoroughly and so well, lo, these twenty-three years gone.

Standing there, I wondered if the Master had ever thought of me again. I’d combed though his later works, hoping to find some refracted image of myself—sometimes imagining that an echo of our pleasures could be found in Bill’s descriptions of farm boys in transports of sexual abandon. I’d even mailed him shameless letters, asking if my speculations were correct. But he never answered, and then one day he died.

“I miss you, Bill,” I said into the plush Victorian quiet of the hotel hall.

I can swear I never touched his old room’s door, but just as surely as if I’d pounded on it with my fist, a voice from within called, “We hear you. Come on in.” The words were blurred, as if the speaker had a lisp.

I pushed forward; the door swung open. The room was filled with heavy, dark furniture, and books piled in the gloom. A man with long, stringy blond hair and a fluffy blond goatee sat before a velvet-curtained window, bent over a desk with a single brass lamp. At first I had only a quarter-view of his face. He was bent very low indeed, as if kissing the papers scattered on his desk, papers covered by penciled writing in the smallest script I’d ever seen.

“Welcome back, Gregge,” came a high, twangy voice, different from the one I’d heard through the door. The blond man turned his head, clamping his mouth tight shut and staring at me with pale blue eyes that held an expression of triumphant glee. A curious high piping seemed to come from within his head. And then all at once his mouth gaped open.

You must believe me when I tell you that his tongue was a small manikin, a detailed copy of William Burroughs, fully animated and alive. I, who have so little imagination, could never invent such a thing.

I stepped back, feeling for the door, wanting to flee and forget what I was seeing. But I struck the door wrong—and it slammed shut. The blond man came closer, mouth open, eyes dancing with spiteful delight. I was shaking all over.

Like a dictator on the balcony of his palace, the meat puppet Burroughs stared out from the mouth, his tiny hands resting upon the lower teeth as if upon a railing.

“I knowed you was coming,” came Bill’s thin, rheumy voice. He was using the Pa Kettle accent he sometimes liked to put on. “Picked up your moon-calf aura from the hall.” He paused, savoring my reactions.

“I don’t understand,” I said, fighting back a spasm of nausea. “Don’t hurt me.”

“I’m working out karma,” said the little Burroughs. “I owe you for never writing back. I’m gonna let my pal Dr. Teage set you up for a Poe tasting. Later on you might do some secretarial work for us—or make yourself useful in other ways.” He allowed himself one of his appalling leers. “You’re aging well, Gregge. But that’s enough outta me already.”

In a twinkling, the Burroughs face on the blond man’s tongue smoothed over, and the tiny arms sank into the pink surface. I was faced with a somewhat seedy character licking his lips. His breath smelled of fruit and manure.

“I’m Teage,” he said, his goatee wagging. “And you’re–”

“Gregge Crane,” I said. “I knew Bill a little, a long time ago. I was with him in this room.”

“I know,” said Teage, who for some reason seemed to trust me. “I’m with him in this room every day. We’re doing a book together. I’m like you. I always wanted to be a fiction writer. Look at this.”

On the desk were the sheets filled with tiny words, and lying on one of the sheets was a sharpened bit of mechanical pencil lead with a scrap of tape around one end. Bill’s writing implement, half the size of a toothpick.

“The process is my own invention,” said Teage. “I call it twanking. Before I started channeling Bill, I was a biocyberneticist. Twanking is elementary. You assemble a data base of the writer’s works and journals, use back-propagation and simulated evolution to get a compact semantic generator that produces the same data, turn the generator into the connection weights for an artificial neural net, code the neural net into wet-ware for the gene expression loops of some human fecal bacteria, and then rub the smart germs onto living flesh. I think it’s deliciously fitting to use my tongue. Bill speaks through me. Every night I twank him by rubbing on a culture of his special bacilli. I lean over our desk and we write till dawn. Afternoons I read it over. I really need to start getting it keyboarded soon.”

“What’s the book going to be called?” was all I could think to say.

“Bill hasn’t decided yet.” Teage hesitated, then pressed on. “The thing is, Gregge, he’s much more than a simulation. I’ve caught his soul? Is soul a bad word anymore? Logically, you might expect that there’d be no continuity of behavior from session to session. But Bill remembers. He’

s all around us—dark energy. He knows things, and even when the visible effects wear off, he’s still inside my tongue.”

Perhaps it was the effects of the champagne—or my pleasure at having Burroughs call me by name—but all this seemed reasonable. And, God help me, it was I myself who suggested the next step.

“Maybe you can help me twank Poe. The whole reason I came out here this summer was because I need to write a story in his style.”

“I know,” said Teage, “Bill and I have been getting ready for you. Bill’s known for months that you’d come tonight. The spirits are outside our spacetime, Gregge, continually prodding the world toward greater gnarliness. Inching our reality across paratime. Making your and my lives into still more perfect works of art.” He let out an abrupt guffaw, his breath like the miasma above a compost heap.

“You’ll give me a germ culture to turn my flesh into Edgar Allan Poe?” I pressed.

“It’s over here,” said Teague. “And maybe tomorrow you’ll start typing my manuscript into your computer. Unless there’s a complete rewrite.”

“Fine,” I said, sealing our deal. “Wonderful.”

The twanking culture consisted of scuzzy crud on a layer of clear jelly in a Petri dish atop a dusty green Collected Works of Poe. Teage fit a cover onto the dish and handed it to me.

“I’ve got no use for this batch myself,” he said. “I’ve got my mouth full enough with Burroughs.”

I peered into the dish. Fuzzy white Cheerio-sized rings. Green and orange streaks. Spots, dots, and streamers.

“You only need a little at a time,” Teage was saying. “Dig out a few grams of the culture with, like, a plastic coffee spoon, and smear it on. Careful where you put it, though. It takes hold wherever it touches. The tongue’s especially good because it’s so flexible.”

Back in my room I brewed a pot of coffee and sat down to record these events on my laptop and on the cute little minidrive that I carry with it. I once lost a year’s work on a Poe bibliography in a hard disk crash, and now I always make a point of saving off my work as I go.

Million Mile Road Trip

Million Mile Road Trip Good Night, Moon

Good Night, Moon Transreal Trilogy: Secret of Life, White Light, Saucer Wisdom

Transreal Trilogy: Secret of Life, White Light, Saucer Wisdom Complete Stories

Complete Stories The Sex Sphere

The Sex Sphere Surfing the Gnarl

Surfing the Gnarl Software

Software Mathematicians in Love

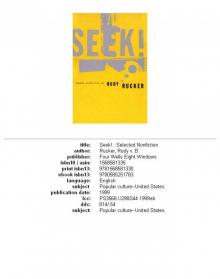

Mathematicians in Love Seek!: Selected Nonfiction

Seek!: Selected Nonfiction The Secret of Life

The Secret of Life The Hacker and the Ants

The Hacker and the Ants Postsingular

Postsingular Spaceland

Spaceland Transreal Cyberpunk

Transreal Cyberpunk Sex Sphere

Sex Sphere Spacetime Donuts

Spacetime Donuts Freeware

Freeware The Ware Tetralogy

The Ware Tetralogy Frek and the Elixir

Frek and the Elixir Junk DNA

Junk DNA White Light (Axoplasm Books)

White Light (Axoplasm Books) Nested Scrolls

Nested Scrolls Inside Out

Inside Out Where the Lost Things Are

Where the Lost Things Are Mad Professor

Mad Professor As Above, So Below

As Above, So Below Realware

Realware Jim and the Flims

Jim and the Flims Master of Space and Time

Master of Space and Time The Big Aha

The Big Aha Hylozoic

Hylozoic