- Home

- Rudy Rucker

The Sex Sphere Page 5

The Sex Sphere Read online

Page 5

"Smeep smeep. Smeep smeep smeep."

The little sphere seemed to twitch, to grow a bit.

"Smeep smeep," went Lafcadio, pausing to grin and nod encouragingly at me. I was supposed to help.

"Smeep," I went, dry lips puckered. "Smeep smeep smeep."

"Smeep smeepy."

"Smeepity smeep smeep."

The little ball grew, its surface flowing. In a way, I felt like I was being hypnotized, or having a hallucination. But yet the . . . presence growing and taking shape in crazy Lafcadio's cupped palms seemed real enough. Another order of reality, I thought, when suddenly . . .

There was the crash of footsteps, an explosion of gunfire, and Lafcadio pitched toward me, his chest gushing blood. With what must have been his last act of volition, he passed the magic sphere to me. It shrank back to the size of an orange-pip. I pocketed it as I stepped back from the intruders.

They were two very short men with guns, burr haircuts and big jaws. They looked like a couple of the "snoids" R. Crumb used to draw, amoral little goblin-men who live in sewers and assholes. They wore matching gray mechanic's overalls with nametags. Orali and Rectelli. One had a machine gun and one had a sawed-off shotgun. They didn't look like police.

Or act like them. The snoid with the machine gun rapidly emptied out Lafcadio's pockets, making a growing mound of newspaper clippings, pages ripped out of books, drawings of circles, pornographic photos, dead flashlight batteries, orange rinds, squeezed-out tubes of ointment, and balls, balls, balls. There must have been fifteen or twenty little balls, some wood, some metal, some rubber. Ball bearings, Ping-Pong balls, bocce balls, gumballs, and even a tiny Earth-globe pencil sharpener. But none of them seemed to be alive like the one I'd pocketed.

The snoid with the sawed-off shotgun stepped over and blasted the chain connecting me to the wall. Pieces of metal and concrete flew up, catching me on my good cheek. It stung viciously. I could feel the wet of blood. I was scared to touch my face, scared that some of it was gone.

They began hustling me out of the room, not noticing that my ankles were still manacled together. I stumbled and fell forward. Somewhere outside, the shrill do-so, do-so, do-so-do-so-do-so of an approaching police car sounded. The shotgun fired off a blast between my legs . . . OH! . . . and then my ankles were free. There was blood and smoke everywhere. I was half-deaf from the gun-blasts.

The snoids got me upstairs, and before I knew it, we were in a purple Maserati convertible, doing 120 kph through Rome traffic, the police somewhere far behind. A beautiful Sophia Loren look-alike was driving. The snoids called her Giulia. It sounded like they were telling her to drive faster.

I was in the front next to Giulia. The death seat, as regards traffic fatalities. Each snoid kept a gun-barrel on my neck. The way the car was whipping around was just unreal. It was like watching Cinerama.

"Please, Giulia," I moaned. "Please slow down."

She answered without looking over. Thank God she had the sense to keep her eyes on the road.

"Calmo."

The full beautiful lips made the second syllable into a kiss. The voice, damped and deepened by two luscious swells of mammary tissue, was like a caress. Poised between two kinds of death, I fell in love. Cautiously I touched my cheek. It was only an abrasion after all, already scabbed over. A stroke of luck.

A bridge flew under us. To the left I could see the Castel Sant' Angelo, beautiful in the mild April sun.

We fishtailed around one of the vegetable-green Roman buses and took a hard right in a controlled four-wheel skid. I wished the car had a solid roof, or at least a roll bar. Giulia was not really a very good driver.

Now we were on a wide street parallel to the Tiber. A nontourist street with cheap department stores and dress shops. A Supercortemaggiore parking garage was coming up on our left. With a horrible wrench, Giulia heeled the car over, cut through three busy lanes of traffic and skidded into the garage entrance. I kept worrying that one of the snoids' guns would go off by accident. Distractedly I put my hands to my face and fingered my scabs.

Inside the garage they seemed to be expecting us. In the rear wall a giant metal mouth yawned open. An elevator for cars. We powered in. And finally stopped. Behind us the two halves of the elevator door whumped together. In the pit of my stomach I felt the descent begin.

"Are you a friend of Virgilio's?" I asked.

"Sometimes. He sold you to us. You will build atomic bomb, yes? We have . . . "

The elevator came to a stop. The doors in front of us slid open like jaws—one half went up, one half went down. Giulia fell silent and jockeyed the car down a dark, empty tunnel and through another automatic door.

"How you fellows making out back there?" I called to the snoids. There was no answer save for the steady pressure of the gun-barrels on my neck. I was so happy not to have died in a car crash that I felt absurdly elated. Build an A-bomb? No problem. I'd read a couple of articles on it in grad school. Now if they just had a glove box so I wouldn't have to touch the plutonium it'd be . . . But what was I thinking?

"OK," Giulia said. "We get out here. You first, Bitter. You get out and up against the wall."

I hesitated. "You're not . . . you're not going to shoot me?"

She smiled beautifully, each tooth a pearl. "Calmo."

I got out, went up to the wall in front of the car and put my hands on it. The skin on my back crawled, but the snoids didn't shoot me. To my left there was a door, and Giulia tapped out a complex tattoo. While we waited, I thought about the mysterious sphere I'd inherited from Lafcadio. I seemed to be able to feel its tiny warmth in my pocket. Later, when I was alone I'd . . .

A peephole opened and closed. With a rattle of bolts, the door swung open. A slight red-haired man and a dark hard-faced little woman peered out over a pair of Uzis. The women talked Italian for awhile, and then we went on in. The snoids stayed outside.

"The only exit," Giulia cautioned me, "is back through this garage. So do not attempt an escape. There is no escape."

"Fine. Fine." I nodded several times. All these guns were making me nervous. I kept my hands at my sides and tried not to make any sudden gestures.

"Peter Roth," the red-haired man said, introducing himself with a quick bow. "Sprechen Sie Deutsch?" He bobbed up and down with a chicken's jerky nimbleness, and turned his head to fix me with what seemed to be his only good eye. I felt like an interesting caterpillar.

"Ja, ziemlich gut," I answered. "Ich wohne zur Zeit im Heidelberg."

"Ach, wie schön. Ich hab da studiert."

"Und was für ein Fach?"

"Mathematik. Zwar Logik und Mengenlehre."

This pleasant little chat about Roth's mathematics studies could have been lifted right from a faculty tea back at the University of Heidelberg . . . though the presence of automatic weapons did stiffen the atmosphere.

The room we were in was, except for one thing, just like the organizational office of any small political party. There were a couple of beat old chairs, a file cabinet, a table with a mimeograph machine on it, a vinyl couch and a desk with a typewriter. The wall next to the desk was covered by a bookcase. There were no windows, of course, but the air was fresh, and three fluorescent light fixtures set into the low ceiling provided a nice even glow. The floor was carpeted in beige, the brick walls were painted cream and the ceiling was covered with soundproof tiles. Two doors led off the office, connecting it on the one side to a sort of one-room efficiency apartment, and on the other to an enormous workshop with machines.

The one thing that made this office unusual was the presence of large numbers of green plants. There was a row of ferns along the top of the bookcase, a huge spiky aloe plant in one corner, a little banana tree in another corner, several hanging pots of flowering fuchsia and numerous small begonias, African violets, geraniums and the like. It was the plants that gave this deeply buried room its fresh, open feel.

Giulia and the other woman were intensely discussing something, so I continued

my German conversation with Peter Roth.

"What's going on?" I asked him. "Why did those schnoids come after me?"

"Virgilio has arranged it. At first he was going to sell you to Minos for a simple ransom. But after the Embassy's reply he realized that you would be valuable to us. He told us where to seek for you. Virgilio's phone is unfortunately tapped, so we had to act in some hastiness."

This raised more questions than it answered. For one: If a deal was made, then why had it been necessary to kill Lafcadio? For two: Why hadn't the Embassy just said that I was an unimportant little physics researcher who knew next to nothing about bombs? Instead they had replied in such a way that Virgilio the trapper could peddle my pelt to . . .

"Who are you? What is your organization?"

"We call ourselves Green Death." In German it came out Grüner Tod.

"Not the Red Brigade?"

Roth shook his head rapidly. "That's all over with. Like the Baader-Meinhof gang. Seventies-years stuff. Green Death is eighties-years."

I was beginning to see why all the plants were hanging around. Green Death. I figured this must be some super-radical splinter of Greenpeace: the people who'd been going around wrecking seal hunts and ramming whaling ships.

"But what do you want with an atomic bomb?" I demanded. "Surely that's not . . . "

"Professor Bitter!"

The dark little woman had finished her conversation with Giulia. Giulia shot me a bone-melting smile and drifted into the connecting apartment. I felt like trotting after her and etcetera. How could any woman have such a thin waist and such wide . . .

"Professor Bitter!"

Roth nudged me, in as friendly a way as possible, with his gun. The boss wanted my attention.

"Yes?"

"I want you to build us a big-ass bomb."

She was only five feet tall, but the voice more than made up for it. It was strong and rough, with a punk-singer's rhythm. Fingernails and black jello. Funny, I had taken her for Italian.

Her skin was pale, with a yellow tinge of liver. Her hair was short, black, spiky. She wore an elastic-waist overall printed in camouflage, and a pair of black combat boots with little gold stars painted all over.

"Of course," I heard myself saying. "Of course, I'm a nuclear weapons expert."

Not only am I scared of big strong men, I'm scared of mean little women. It's just little skinny men and nice big women that I get along with. People like Roth and Giulia. I was sorry to see this woman here at all. "What's your name?" I demanded with a trace of reckless insolence.

"Beatrice." She used an Italian accent on it. Bay-ah-tree-chay. "I am the pistil of the Green Deathflower. You will be our thorn."

"The thorn of plenty," Roth put in, managing to speak a clean, German-American English. He had laid down his gun somewhere. Perhaps Giulia had taken it into the little apartment, now closed.

Glancing over at Peter, Beatrice smiled for the first time.

"Thor'n likely."

"Thorn-Burger Deluxe."

"Thornium-233."

These were strange people. But suddenly I felt relaxed enough to smile too.

"What is this Green Death stuff anyway? What are your goals?"

"The human race is a blight. A cancer-virus eating at Mother Earth. We want to blow it all away. Radiation therapy."

"People are part of Nature, too," I objected. "Some say the best part."

"Even in Antarctica they can smell our stink," Peter intoned. "The great oceans are polluted. And on the land the deserts grow. Every day another species becomes extinct. Human civilization must be stopped before all is lost."

"It's going to take more than one bomb to bring down a global civilization," I said noncommittally. If Roth and Beatrice had seemed friendly a minute ago, they were all business now.

"You leave that to us," Beatrice snapped. "You just build us our bomb. Show him, Peter."

Roth started to steer me into the huge workshop off the little office, the room with machinery in it.

"Wait," Beatrice cried. "Keep a gun on him, Peter."

"Ja, ja." He walked over to the little apartment door and opened it. The smell of frying meat came out. My head swam with sudden hunger.

"Could I . . . could I have some food before starting on your bomb?" Food and drink and a wash and a piss and a rest . . . I needed them all. "I feel very weak."

Beatrice gestured with her machine gun. "OK. Go on in there and eat. I'll keep you covered."

It was a pleasant lunch. Giulia had fried some veal scaloppini in a little Marsala. She and Peter and I had them with mounds of al dente spaghetti loaded with butter and Parmesan. There was some rough red Valpolicella wine, and I drank as much as they would give me . . . which wasn't as much as I would have liked. By the time we got to the coffee, Beatrice had relaxed enough to sit down and join us.

Over the coffee, the four of us began to chat. We started with neutral topics: world travel, European trains, the sights in Rome, my research work. From my research I got onto my recent history: how I had lost my job in America but gotten a grant to study in Heidelberg. Before long I was even talking about my childhood as a smart, lonely kid in Kentucky.

Having to hear someone else's life-story makes people want to tell their own. Before long we had a regular encounter group going. Giulia get out the Valpolicella, and over the next couple of hours the three Green Death terrorists told me about their lives, and about how they'd come to Rome.

Chapter Five: Three Statements and a Mental Movie

The Story of Giulia Verdi

"I grew up on a farm near Verona. My father raised plum tomatoes for canned paste, and grapes for cheap wine. The soil was dry and rocky. There was always sun, and the leaves were covered with fine white dust. The vines could find their own water deep underground, but the tomato fields needed constant watering. When the sprinklers were on, I loved to run down between the dripping rows of tomato plants, smelling the acrid leaves and the settling dust.

"My twin brother Ugo was always with me. In the spring we would help Papa's men graft the new scions onto the gnarled vine-stocks. And when the tomatoes started growing, we would pick off the worms. But there were many summer days when we had nothing to do but run and play.

"Ugo was saving up money to get a racing bicycle. He was always listening to bicycle races on the radio. Sometimes I would help him make money by searching for bottles and scrap metal along the railroad track. The track ran right next to our property. There was a crossing and even a little old man living in a house to raise and lower the gates. He liked to tell us terrible, blackly funny stories about the war.

"I had an older sister, Maria, who became a nun. She lived in a nunnery in Verona. One summer my body began to develop. It came too early. Men stared at me, and I was frightened. Mama sent me to spend a month safe with Maria.

"While I was gone, a train derailed onto our property. There was a tank-car full of some poison. An ingredient for a pesticide. All my family died, all our animals, all our plants. It is so poisoned there that it is still fenced off. They pushed dirt over the broken tank-car, and no one can go close.

"Maria said I should go to the University and become a doctor. She said I should put the past behind myself. And I did study; I studied for years. I became a psychiatrist for working people in Mestre. This is an industrial town near Venice.

"I noticed how similar the psychoses of my patients were. A whole world of madness seems possible to the layman, but the doctor sees only the same few blighted fruits: depression, paranoia, dissociation. Those whose jobs force them to work with toxic materials have much higher incidences of mental illness. Why must such products be produced? Whom do they really benefit?

"Over the next few years I became increasingly involved in environmental activism. I marched, I collected signatures, I lobbied for legislation. But still the air hurt my lungs, and still the corroded stones of Venice sank deeper into the sea. It seemed that no one could stop the criminal polluters.

"One of the terrorists was captured: Beatrice. She pleaded insanity. The court assigned me to interview her. I found her the only sane person in Mestre. We joined forces."

The Story of Peter Roth

"I grew up in a village near Essen. I was an only child. My parents ran a little food store. Wine and canned goods, and fresh things. Milk, bread, vegetables. Every morning my father would get up at 4:30 and drive to the farmers' market. He had the best vegetables in the village.

"My mother's father had been a hunter, in charge of a noble family's woods. She loved the forest and knew the names of all the plants and insects. When I was little we took many walks. But soon the forests near us were all gone. On Sundays Father would drive us on the autobahn in his Mercedes. That was his great love, driving the Mercedes.

"Finally there was a crash. A VW was trying to pass someone, and we plowed into him from behind. Mother died; we had to watch her, with metal in her chest. It was horrible.

"I worked in the store after school. The women in the village were all kind to me, but I was very lonely. At night I studied, I studied hard so I could get my Abitur and go to the University. Ever since the accident I hated my father.

"I went to Heidelberg. The German university life is very free. No one keeps track . . . you simply attend the lectures that you choose. I had saved some money, and father helped me too, so that I could rent a room in someone's basement. The first year I spent Christmas with my new girlfriend's family. I didn't go home until Pentecost—and what I saw was very surprising.

"The coal strippers had taken away our village. They have a machine; it is as big as the cathedral at Worms. They have such a machine with a whirling disk of diggers that shaves the land away. A rich seam of coal lay under our village, you see. One of the big companies had bought the mineral rights, and they just left an open sore where I had lived.

Million Mile Road Trip

Million Mile Road Trip Good Night, Moon

Good Night, Moon Transreal Trilogy: Secret of Life, White Light, Saucer Wisdom

Transreal Trilogy: Secret of Life, White Light, Saucer Wisdom Complete Stories

Complete Stories The Sex Sphere

The Sex Sphere Surfing the Gnarl

Surfing the Gnarl Software

Software Mathematicians in Love

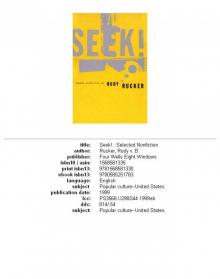

Mathematicians in Love Seek!: Selected Nonfiction

Seek!: Selected Nonfiction The Secret of Life

The Secret of Life The Hacker and the Ants

The Hacker and the Ants Postsingular

Postsingular Spaceland

Spaceland Transreal Cyberpunk

Transreal Cyberpunk Sex Sphere

Sex Sphere Spacetime Donuts

Spacetime Donuts Freeware

Freeware The Ware Tetralogy

The Ware Tetralogy Frek and the Elixir

Frek and the Elixir Junk DNA

Junk DNA White Light (Axoplasm Books)

White Light (Axoplasm Books) Nested Scrolls

Nested Scrolls Inside Out

Inside Out Where the Lost Things Are

Where the Lost Things Are Mad Professor

Mad Professor As Above, So Below

As Above, So Below Realware

Realware Jim and the Flims

Jim and the Flims Master of Space and Time

Master of Space and Time The Big Aha

The Big Aha Hylozoic

Hylozoic